In The Shadow of The Brutalist

A good friend of mine, Max Scholl, recently published a scathing review of Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist in The Rice Thresher (Rice University’s equivalent of the Daily Pennsylvanian). He called the film a bloated, “pretentiously segmented” exploration of tortured genius. While I understand his frustration, I think he’s missing the point of the film. Yes, The Brutalist is long. It’s pretentious. It’s ambitious and unapologetically grand. But this is what makes it interesting. It’s a film that forces you to bear witness to an unchecked ego and sit with that discomfort. Far from being a stock tale of genius, the film is a complex (and flawed) meditation on the forces that can elevate and destroy a man.

Scholl’s review raises valid concerns, to be sure - the film is undeniably long (nearly four hours), fragmented (though intentionally so), and wears its themes on its sleeve, but to reduce it to a mere exercise in self-insistent cinema is to miss the broader ambitions and, frankly, the complexity that Corbet weaves into the narrative. The film does more than tell the story of László Toth, the visionary architect of monumental structures while struggling with the pressures of a new world, centered in Doylestown, a Philadelphia suburb. It’s an exploration of what happens when ambition transcends human capabilities and becomes an isolating, self-destructive force.

Essentially, it’s about the cost of genius - on the individual, their relationships, and the world around them. It’s not a celebration of genius. Scholl’s review brushes aside this nuance, calling the film’s ambition pretentious. He criticizes the four-part structure and 15-minute intermission as indulgent and over-the-top. But what he misses is that the film’s grandiosity mirrors the subject: the towering vision of a man who is willing to sacrifice everything - including himself - for a vision of beauty transcending time. The film’s length and structure reflect the size of Toth’s ambitions; if anything, these formal choices emphasize the isolation that comes with single-minded pursuit.

_______

Doylestown feels caught between eras. Frozen in some ways, pushing forward in others. Stuck in a liminal space. The Mercer Museum, designed by the enigmatic Toth-esque Henry Mercer, captures this tension. Walking its cold hallways, surrounded by century-old tools and artifacts, I glimpse the ghosts of a past world. Each tool tells the story of someone who used it with purpose, who built something that seemed permanent. What is it we build, and what stays? It’s humbling to stand there, surrounded by the weight of labor, and think about how much of my work is fleeting, chasing after something that will fade before any of us have time to understand it. The walls remind you - nothing lasts, everything leaves a mark. We’re supposed to admire, even revere the past, but never live in it.

I keep walking. I try to imagine the people who used these tools, what their lives were like, how their work shaped the world. But their lives seem distant, and as much as I try, I can never truly inhabit their world. I walk through the halls. I’m standing in a place that can’t belong to me, even as it invites me in. I can’t quite articulate the feeling, but it lingers: the quiet sense that the museum, the town, the history it holds are both mine and not mine.

I walk down the streets outside. The town seems caught between the weight of history and the modern lives that unfold within it. Old buildings loom, heavy with size and stories. But there’s lightness, too - a sense of life moving forward. The past is just under the surface, pressing in, refusing to let go. I think of the Mercer Museum’s gray walls, its silent gaze. It asks us to stop and feel the weight of what came before. But in the next breath, it challenges us to question what we’re building and what we’re leaving behind. It’s impossible to stand in this place. The past is always there, but it doesn’t want us to stop moving forward.

That’s what I can’t shake. That’s what keeps me coming back, walking through this town, standing in the shadow of a past I’ll never understand. Everything here is waiting for something else - some final moment of realization, some reckoning. There’s something oddly hopeful about that, even as we all run out of time. Each time I visit, I’m piecing together a puzzle, one small piece at a time - of a place, of a history, and a life that doesn’t belong to me. But still, it’s a part of me.

_______

The opening scene, which Scholl highlights as stunning - and I agree, - is key to understanding the film. It’s a long, drawn-out shot of Toth arriving at Ellis Island while a letter from his wife Erszebet is read through voice-over. The camera lingers on his arrival in the United States capturing both his physical and mental displacement - the core conflict of the film. This is not a traditional narrative beginning, but rather a slow, meditative look at the individual in the face of a monumental task. The Brutalist asks us to consider how the soul of a man becomes consumed by the ambition to create something grand - a project so large that it can only exist as a monument to his genius, devoid of humanity. In this sense, the film is not about Toth’s rise to success, but about the internal rot that occurs when a person prioritizes vision over well-being.

Scholl’s reading of the film as a simplistic tale of the tortured genius overlooks the nuances of Toth’s character. Toth is not a hero, nor is he portrayed as one. He is a flawed man whose ambition blinds him to all suffering - his own and of those around him. His personal relationships - especially with women - are not secondary in a way that ignores their importance, but in a way that reflects how Toth sees them: as a means to an end. His interactions are marked by distance, and he treats them as objects to be molded around his ambitions. It’s a dynamic that the film certainly interrogates; rather than simply portraying Toth’s egoism as a sad but necessary trait of the great artist, The Brutalist makes it clear that genius is an inherently isolating force. It’s destructive. It’s suffocating.

Scholl’s critique of the film’s handling of women feels like a superficial reading. He argues that the women are relegated to subservient roles, existing only in relation to Toth. This is true, to an extent, but Scholl’s failure to ask why this is the case misses the mark. The women in The Brutalist are not just plot devices. His off-hand dismissals of his wife Erszebet and niece Zsofia reflect Toth’s distorted worldview, existing more as fragments of his vision than as fully formed characters. His relationships with them act as mirrors, exposing his failure to see beyond his own grand design. It’s not just misogyny - it’s a deeper critique of his inability to connect with anyone outside his intellectual bubble. The film isn’t glorifying his treatment of women - it’s making clear that this is the consequence of unchecked ambition. In this way, The Brutalist works as a critique of the kind of blind genius that ignores the human cost of progress.

_______

Fonthill Castle rises from the woods like a dream - or a nightmare, depending on the light. From afar, Mercer’s home almost looks like a ruin, its concrete walls crumbling, towers leaning in ways that defy convention. But up close, it’s alive with detail. Tiles pressed into every surface, staircases twisting in strange directions, rooms stacked like mismatched puzzle pieces. It’s hard to see where one thing ends and another begins. Like its creator, the castle is elusive - brilliant and unsettling, controlled and chaotic.

There’s something unsettling about walking through it. The rooms are cramped, the ceilings low, and every corner holds a secret. It’s hard to navigate. Mercer’s obsession is everywhere - in the tiles, the books, the deliberate strangeness. It’s a space that doesn’t let you forget its maker, as though the walls are whispering his name. And yet, it feels fragile. The cracks in the concrete, the light filtering through dusty windows - even monuments crumble eventually.

But maybe that’s what Mercer wanted. The castle isn’t a place that tells you what to think. It forces you to sit with its contradictions: beauty and decay, control and chaos, permanence and impermanence. The Mercer Museum tries to hold the world in place, cataloging every artifact it can get its hands on. Fonthill feels more personal, like it’s holding onto something less tangible. Not history, but something closer to a feeling - a kind of restlessness, a refusal to let anything stand still.

It’s easy to get lost in the castle. The staircases don’t lead where you expect them to, the rooms double back on themselves, and the layout defies logic. Mercer didn’t build Fonthill to make sense, but rather to challenge the idea of sense. To walk through the castle is to confront the limits of understanding, to let go of the need for resolution.

And still, Fonthill feels complete. Every crack, every crooked corner, every misplaced tile - it all fits together. Meaning isn’t always built out of coherence. Sometimes it’s built out of the act of creation itself, the process of building something out of nothing, even if that something doesn’t make sense to anyone else.

But as I said, the castle is unsettling. It feels less like a home and more like a labyrinth, a place built to trap. I wander its halls. I can’t shake the feeling that I’m being watched. By Mercer? By the castle? I can’t understand this place. I leave. I feel like something’s missing. Fonthill is part of a bigger picture, a piece of a puzzle I haven’t cracked. It holds onto its mysteries. I need to sit with these questions.

_______

Scholl brings up the film’s treatment of masculinity. He claims that The Brutalist glorifies Toth without critique, but this conclusion misses the point. The film is not celebrating his masculinity; it’s exposing how deeply ingrained and toxic his self-perception is. There are moments where Toth’s arrogance and self-importance are on full display, and his machismo is impossible to ignore. But these moments aren’t presented as heroic; they are a means of examining how masculinity, when brought to an extreme, becomes a prison. Toth’s drive to create something eternal is inherently tied to his need for validation to prove his worth as a man. It’s not just about creating something beautiful, but about creating something that proves his value to the world and to himself.

Scholl’s reading of the film as an attempt at postmodern self-reflection is accurate, but he doesn’t acknowledge the complexity of what’s being said. The film is not merely engaging in irony or a superficial critique of modernity but is addressing how historical and cultural forces - nationalism, xenophobia, the Holocaust - shape a person’s vision for the future. Toth’s work is more than architecture; it’s the construction of a new world order rooted in his vision of absolute truth and beauty. But this vision is entirely detached from the reality of the world around him. As Scholl notes, the film examines America’s rise as a global superpower, but it does so through the eyes of an individual detached from the forces shaping the future. Toth’s genius, which he sees as a force for good, is really just his failure to engage with the world as it is.

I agree with Scholl’s reading of the film’s historical context, but not his interpretation. He calls it incoherent in its portrayal of the 20th century, but that’s exactly what makes The Brutalist stand out. Corbet refuses to offer a coherent or easy reading of history; he captures the confusion and disorientation of a post-war world in flux - a world where trauma, political upheaval, and the promise of a better future are in constant tension. The film’s treatment of the Holocaust, American xenophobia, and the evolution of technology is not meant to be a straightforward historical analysis; it’s meant to show the violent collision of these forces within Toth’s mind as he attempts to build something beyond them all.

_______

Henry Mercer might have been the most unusual man in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Or anywhere else, for that matter. He doesn’t fit into any neat categories, which seems fitting for someone so obsessed with the messy sprawl of history. An archaeologist, an artist, an architect - labels don’t stick to him for long. Even his legacy feels slippery, shifting depending on which one of his creations you’re standing in. In the Mercer Museum, he’s the historian, cataloging the tools of a vanishing world. At Fonthill Castle, he’s the architect, the eccentric dreamer, building a house out of concrete and chaos.

But Mercer the man remains elusive. His works speak loudly, but he himself was quiet, solitary, intensely private. There’s a tension between the magnitude of what he left behind and the silence of the man himself. He poured everything he couldn’t say into his creations, letting the objects, the tiles, the architecture do the talking for him. And what they say is complicated.

To study Mercer is to study contradiction. He revered the past, yet he built with concrete - a material of the future. He preserved artifacts meticulously, yet his own creations seemed designed to crumble, to decay. Even his role in history feels complicated. He lived through the Second Industrial Revolution and seemed to loathe what it represented - the erasure of individuality, the standardization of daily life. But his wealth and privilege, born from that same industrial machine, gave him the freedom to create. He was both a critic and beneficiary of industrialization.

Mercer’s obsession with control is clear. Despite all he accomplished, he is always reaching for something more. He wanted to preserve history, but time wouldn’t hold still. He built his museum and castle, but even concrete crumbles. He sought to understand the world, but his creations reveal a man who never found the answers he was after.

There’s something inspiring about that restlessness. Mercer didn’t let the impossibility of his goals stop him. He built anyways, collected anyway, created anyway. His work isn’t perfect, but it’s alive with defiance, a refusal to accept the limits of understanding. He knew he couldn’t save the past, but he tried. He knew his buildings would decay, but he built them.

I think about Mercer. I see him as a reflection of his creations. Like his museum, he tried to hold onto a world that was slipping away. Like his castle, he was full of contradictions, cracks in the facade. And like both, he left something behind that refuses to be understood, something that keeps its mysterious close.

Mercer doesn’t offer answers. He’s another piece of the puzzle, another question to sit with. But in his contradictions, in his restlessness, there’s truth. The search for meaning isn’t about finding easy answers. It’s about the search itself, about the act of creating, of questioning, of reaching for something more.

_______

Scholl calls The Brutalist a “case study” of a historical moment, and I agree with him on that. But there’s more to the film than that. Beyond history, it’s a meditation on the human cost of ambition. It’s a critique of the egoism that drives the desire for greatness. Toth’s architecture - so grand, so imposing - becomes a symbol of everything that is wrong with the pursuit of immortality through creation. The Brutalist doesn’t just interrogate the allure of genius - it dismantles it, revealing the ruins in its wake.

In this light, Scholl’s reading of the film as a critique of modernity and its historical entanglements is correct, but I disagree with his interpretation. To reduce The Brutalist to an incoherent series of themes overlooks its deliberate refusal to impose order on chaos. Corbet captures the disorientation of a fractured post-war world, where trauma, nationalism, and rapid progress collide in Toth's blinkered perspective. The film forces us to confront the dark side of ambition and genius, not as heroic forces, but as destructive obsessions. This is not an easy narrative to swallow, nor is it meant to be. That difficulty is where the film’s power lies: in its confrontation of the myths we tell ourselves about creation, greatness, and legacy.

_______

Kilns standing like sleeping giants. Brick surfaces darkened by decades of heat. The scent of damp clay in the air. The metallic tang of old tools stacked in shadowed corners.

The Moravian Pottery and Tile Works feels like Mercer’s purest expression. It’s his heart, laid bare in concrete and clay. If the Mercer Museum is his mind - categorical, overwhelmed by the weight of that past - and Fonthill Castle is his soul - wild, fragmented, desperately searching - then the Tile Works is where his hands speak. Every tile pressed, glazed, and fired here carries the mark of human imperfection. Each one is a deliberate rejection of the mechanical, the industrial, the mass-produced.

Walking through the Tile Works, it’s easy to lose yourself in the rhythm of creation. The old kilns, the earthy smell of clay, the faint echoes of past craftsmen - it all feels timeless, almost holy. Mercer wanted this place to be a living artifact, a museum where tradition could endure against progress. And endure it has, though not without its scars.

The tiles are a study in contradiction. Humble, with no sleek lines or polished surfaces, yet they demand attention. Their imperfections give them life, a quality machine-made objects lack. Rooted in tradition, but experimental, unafraid to be strange and unsettling. Mercer wasn’t just preserving a craft - he was reshaping it, reforging it.

The Tile Works is more than a workshop. It’s a quiet, stubborn resistance to modernity. Mercer’s tiles remind us of the human hand, the labor and care behind making something real. They’re a reminder of what we lose when we trade the imperfect for the efficient, sleek, sterile.

But there’s tension here, too. For all its celebration of individuality, the Tile Works is an act of control. Every tile pressed into its mold, every glaze applied, every firing timed to perfection - it’s all guided by Mercer’s original vision. He wanted to preserve the past, but he couldn’t help but remake it in his image. The tiles are his, as much as they are a product of tradition.

I stand among the kilns and tiles. The Tile Works, like Mercer’s other buildings, is a monument to impermanence. The tiles will crack, the kilns will cool, the clay will crumble. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. But there’s a quiet defiance in this fragility. Mercer knew he couldn’t stop time, but he pressed his vision into the clay anyway. A tile cracked clean down the middle rests on a shelf. Its glaze fades into pale, earthy tones.

The Tile Works is a reminder that creation is always an act of resistance - a refusal to let the past disappear, a refusal to let the present consume us. The tiles resist sterility. They carry the mark of human hands, defying the mechanical. In the cracks and imperfections of the tiles, there’s a truth Mercer never stopped searching for, a truth that’s just out of reach. The tiles aren’t answers. They’re questions, pressed into clay, waiting for us to make sense of them. Or maybe they’re not waiting at all. Maybe they know that the question is enough.

_______

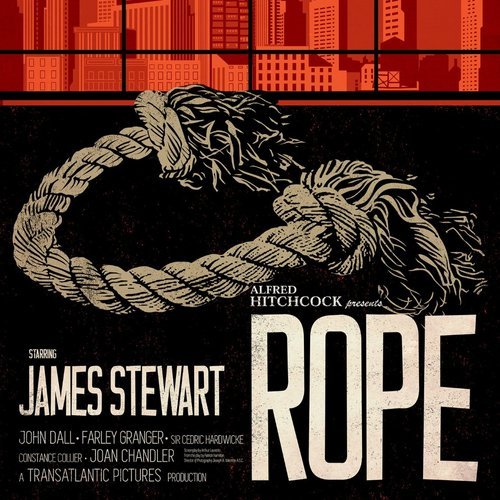

I can’t help but think back to the day I met Max. We toured the University of Chicago together. We were 16 or 17 then, wandering through the campus, wide-eyed and caught between the excitement of possibility and the weight of institution and history. At one point, we found ourselves standing outside the Regenstein Library, staring up at its massive, blocky facade. Max turned to me and said, “I fucking hate brutalist architecture.” I laughed. At the time, it seemed like some post-ironic declaration, something said to fill the awkward silence between two introverted, nerdy teenagers.

But I kept thinking back to what he said. There was something instinctive in his reaction, something visceral, as though he wasn’t just disdainful of the building itself, but of everything it stood for: the weight of history pressed into concrete, the sheer indifference of its towering presence, the way it seemed to loom over us rather than invite us in. Max’s reaction mirrors something Mercer must’ve felt about industrial modernity. The cold mass of concrete. Mechanical sterility. Channeling resistance into craft and clay.

And after sitting through Corbet’s The Brutalist, that moment feels like more than an offhand comment. It feels like a premonition - a rejection, not just of architecture, but of the kind of self-aggrandizing vision to which his film holds so tightly. What Max saw in the Regenstein is, in many ways, what I see in Corbet’s film: a cold, immovable monument to an ideal that, in its quest for transcendence, forgets to consider the humanity crushed beneath its weight.

The Brutalist insists upon its own reckoning. It challenges, provokes, overwhelms, and certainly never compromises. Corbet constructs his narrative with much the same precision and weight as Toth’s architectural vision - a vision shaped not only by the drive for artistic immortality but also by knowledge of the fragility of relevance. The Brutalist is indulgent, monumental, and exhausting, but that’s the point. Great art doesn’t make you comfortable. It confronts you, towers over you, and forces you to grapple with its enormity. But how does the artist grapple with the impermanence of their creations? It’s the same issue Mercer struggled with. Monumental, unyielding forms wrestling with modernity. The creation of alienating spaces. Toth, Corbet, Mercer. They all want the same thing. To shape the world, even as it evolves beyond their grasp. To forge a legacy that defies time.

Max’s disdain for brutalism might have been visceral, but it also gave voice to something undeniable: the tension between awe and alienation, between attraction and resistance, that defines Corbet’s film operates in that same space, offering a stark and unflinching meditation on the human condition - one that is unapologetically massive, angular, and carved out of stone. The Brutalist isn’t for everyone, but for those willing to stand in its shadow, it offers something rare: a vision that dares to be eternal.

_______

Logan, my girlfriend of three years, lives in Doylestown. She notices things I often miss. She has a subtle awareness that makes the world feel different, to me at least. She catches the texture of shadows, the weight of silence in an old room, the way light filters through uneven glass, casting soft patterns on the floor. We visited the Mercer Museum on a gray, rainy afternoon in late December, the kind of day that seems to hold its breath.

Inside, the dimly lit halls were endless. Each turn revealed another relic - old tools, lanterns, a harpsichord missing its strings. Logan lingered in front of a collection of worn saddles. Knowing her affinity for animals, I imagine she was wondering about the horses they once sat upon. I watched her as the muted hum of footsteps and whispers filled the air. Her awareness echoes Mercer’s sensitivity to the imperfect beauty of the craft. What’s most human lies in the flaws, the weathering we tend to overlook.

The Mercer Museum feels like a map to that aforementioned truth, forever out of reach. Every object is a piece of that puzzle, and yet the connections between them were elusive. I think that’s why I return to this space in my mind; Mercer didn’t design his museum to provide answers, but to pose questions. What remains when we strip things down, tear them apart? What’s the weight of memory?

Logan and I wandered to the upper floors. The light danced faintly through narrow windows. We stood together by a collection of blacksmith tools, our breath misting in the cold air. I wondered aloud what the last thing the blacksmith had built was. I wasn’t talking about the museum, and I think Logan knew that.

Mercer’s collection is a monument to unfinished stories, to the impossibility of capturing everything, yet the necessity of trying anyway. Like the saddles, each one bearing silent testimony to what it carried, the horses it burdened, and the hands that once cared for it. I took Logan’s hand. She rested her head on my shoulder. We make meaning not by finding answers, but by creating spaces where the questions can live.

The museum’s quiet chaos demands patience, engagement, and a willingness to see the beauty in fragments. We can’t insist on answers or resolution, on categories or neat little boxes. The answers don't matter as much as the act of searching.

Logan squeezed my hand. We made our way back down the winding stairs. Outside, the rain had stopped, leaving the concrete shining and raw. Mercer didn’t solve the mystery, and neither did we. It doesn’t matter. We keep walking, hand in hand, through the labyrinth.

Popular Reviews