I Want 'Em Conscious And Talkative: The Long Good Friday

Growing up in England in the seventies, I remember watching the grainy news footage of carnage caused by Irish sectarian violence. I’d later witness it firsthand when I moved to London as a student in the nineties and was near enough to hear one of the bomb blasts blow hundreds of windows out of a skyscraper. I still don’t understand many of the complex historical intricacies of the Irish Republican Army’s motivations, but I do know that their domestic terror activities on mainland England hung like an ominous specter over much of my adolescence.

”I'm setting up the biggest deal in Europe with the hardest organization since Hitler stuck a swastika on his jockstrap.”

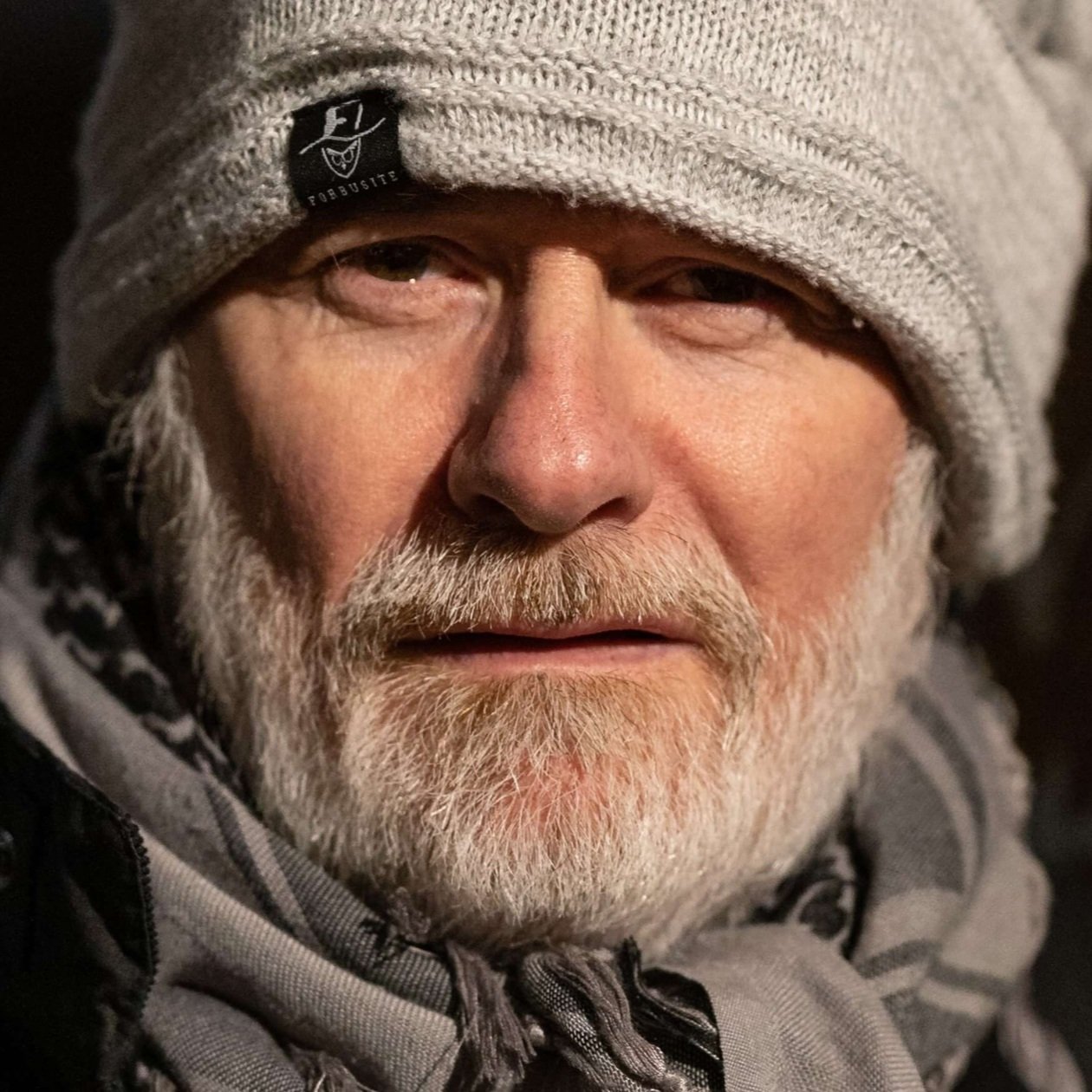

This is the social backdrop for one of the best British movies ever made, The Long Good Friday, which pits the financial motivations of London’s gangsters against the political actions of the IRA in the early 1980s. It would introduce the world to George Harrison’s Handmade Films, which went on to make some of the most wonderful British movies of all time, including Withnail and I, Time Bandits, and Monty Python’s The Life of Brian. It also introduced the world to Bob Hoskins, for whom it would launch a career in Hollywood. It also features a cast of young actors who would go on to become household names, including a mid-twenties unknown, but future James Bond in Pierce Brosnan, in a minor but consequential role as one of the Irish terrorists. The cast list reads as a who’s-who of British actors who would go on to dominate cinema on both sides of the Atlantic.

”Well, let's put it this way. Apart from his arsehole being about fifty yards away from his brains, and the choirboys playing hunt the thimble with the rest of him, he ain't too happy.”

The plot is simple, but violent. Hoskins plays gangster Harold Shand, who controls a crime syndicate centered in East London which reaches as far as New York. He’s surrounded by an inner circle of associates, including Helen Mirren’s Victoria, who plays the role of sophisticated moll to wonderful effect. Derek Thompson, who never did much again in the movies but who’d go on to become a household name every Saturday evening as the star of the BBC’s long running hospital drama Casualty, is Shand’s fiercely loyal right hand fixer, who ultimately makes the mistake which leads to the whole house of cards tumbling down. Shand’s empire aspires towards international expansion through partnership with the American Mafia, but faces increasingly violent attacks at home. Informers are killed and properties blown up as the IRA targets Shand’s activities not for financial gain but for revenge. It’s only revealed late in the film, but as Shand realizes why he’s being targeted, he attempts a reconciliation with the Irish, but double-crosses them, thinking that he’s put his problems to rest. The film ends with another double-cross, this time from the Irish, who hijack Shand’s car and drive him away, presumably to his death as the credits roll.

”I'm glad I found out in time just what a partnership with a pair of wankers like you would've been. A sleeping partner's one thing, but you're in a fucking coma! No wonder you got an energy crisis your side of the water!”

British gangster movies weren’t anything new in 1980, but they’d never been made quite like this before, and they sparked a wave of realism which would reach its peak with films such as Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch, both of which owe a great debt to The Long Good Friday. Hoskins is wonderfully sinister as the threatened kingpin, always with the promise of violence bubbling away underneath the surface. British gangster films, especially those set in London, always deliver some of the best dialogue, my favorite being when Shand is in the morgue looking at the dead body of one of his murdered associates, discussing how to safely dispose of the body. They decide to take the body away in an ice cream truck to avoid suspicion, where Hoskins utters a wonderfully sarcastic improvised line "There's a lot of dignity in that... going out like a raspberry ripple". It would become a trope of British gangster movies that an audience could come to expect dialogue infused with this sense of dark humor.

”It must've been just after you saw him and just before Alan saw him. Otherwise, you'd have noticed, wouldn't you? I mean, a geezer nailed to the floor. A man of your education would definitely have spotted that, wouldn't he?”

There’s also some fantastic set pieces through the film, such as when Shand tells his assembled guests as they cruise down the Thames on his private yacht of his entrepreneurial aspirations towards doing business in Europe, something which reflected a deeply optimistic Thatcherite spirit of the times but would dissolve into the divisive chaos of Brexit many years later. And true to all gangster films, there always has to be a torture scene where the protagonist interrogates his suspects. Here it’s Shand and his thugs dangling a number of poor unfortunates upside down on icy meat hooks as he probes them for information. Underneath it all is a strong sense of English exceptionalism, sometimes to the point of implied racism on Shand’s part, which underpinned the spirit of the times as Britain transitioned to a more multicultural population, especially in London. Those of color are treated as subservient and often treated violently, as are women, who play very little role of consequence in the film. It’s noticeable for modern audiences the extent to which these issues of immigration are still present.

”What I'm looking for is someone who can contribute to what England has given to the world: culture, sophistication, genius. A little bit more than a hot dog, know what I mean?”

Both Shand’s criminals and the IRA use violence to achieve their ends, but their ends could not be more different. Where money is everything for Shand’s gangsters, it means nothing to the Irish terrorists. Politics is simply a corruptible opportunity towards economic prosperity for Shand, but for the IRA politics is a struggle towards justice to be served and historic wrongs to be set right. Murder is a common weapon, and the fear and intimidation used by both sides is everywhere. If Hoskins carries the film as the brash, showy principle gangster, the Irish organization are nameless, often faceless, and operate in the shadows. Brosnan plays one of the Irish foot soldiers, and is only memorable to modern audiences because of what we know of his future career.

”Remember, scare the shit out of them, but don't damage them. I want 'em conscious and talkative. And lads, try and be discreet, eh?”

While The Long Good Friday is absolutely a product of its time, it is at its core, just a great story of deception, greed and violence, with early eighties London itself one of the main characters. In the final shot, Hoskins’ Shand is being driven away to his fate at Irish gunpoint, and the camera lingers on a tight shot of him considering his next move, which we as the audience know will be futile. Led away to die as the cycle of violence continues. But this uncomfortable shot is reflective of the movie itself. It’s claustrophobic, calculated, and seethes with anger. But it’s also recognition that when the game is up, you are resigned to accepting your fate. Whoever you are.

Popular Reviews

![Three Essential Black Mirror Episodes for New Viewers [SPOILERS]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/608d9ef497633c6b6eb71caf/1620754679358-1W0DAR492IZLWOAV28J9/a27d24_dbbb6890773a4d818a88751169d459e6_mv2.jpg)