My One & Only Love: Leaving Las Vegas

Every time I go to Las Vegas, usually for work to spend time in a light-locked, soulless conference room listening to the obvious masquerading as professional advice, I think the same thing. That there’s a deep, longing melancholy to the place. A sadness behind the bright neon lights of the strip, the omnipresent din of the casinos, and the faces of those who’ve come to Sin City seemingly to let loose and get away from it all. Far from the oasis in the desert in promises, the city aches with loss. An unfulfilled hope of gambled pleasure, and drawn like moths to the flame by the flashing billboards, and where darkness never truly descends, we wander around in the half-light neon glow of the desperate attempts to separate us from our time and money.

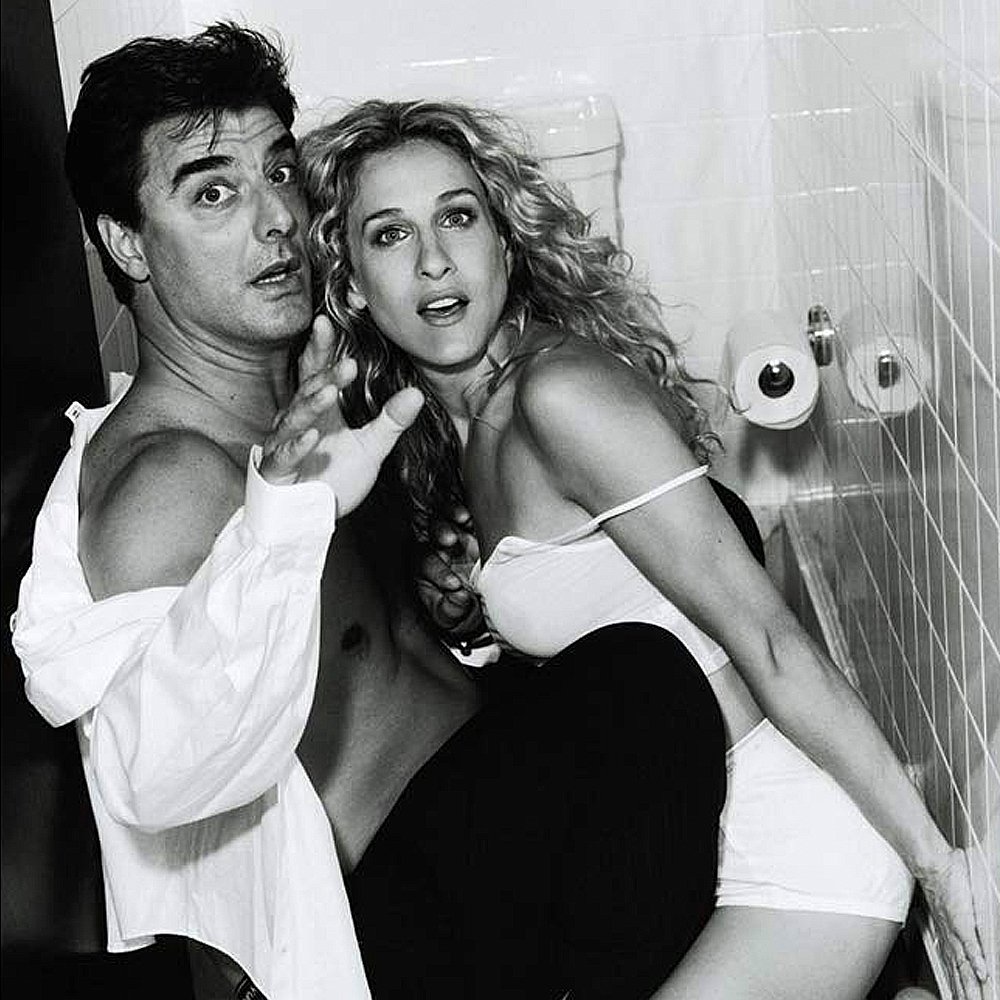

Mike Figgis’ 1995 Leaving Las Vegas bottles these feelings, distilling them into a tragic, romantic, hopeless tale of two lost souls who find themselves on The Strip, find each other in life, and find their eventual love an impossible hope. I usually give most Nicolas Cage movies a wide berth, although I loved him in Wild At Heart, and secretly long for more Cage / Lynch pairings. He was also wonderful in Adaptation as Charlie Kaufman’s blocked screenwriter. But for the most part, the three or four movies he seems to be able to crank out each year I safely scroll past without too much thought. Here he plays Ben, a chronic alcoholic whose life is swiftly spiraling out of control as his disease exerts a stronger and stronger grip on his life. We see his career and family implode, and as he collects his severance from his employer, he’s asked ‘What are you going to do now?’ to which he famously responds in the line that launched a thousand trailers, “I thought I’d move out to Las Vegas”. His plan is a simple one, drink himself to death in a planned and highly managed way, expiring at the point by which there’s no more money left to drink. He holds a fire sale of all his belongings, burning his family photographs, books himself into the cheapest of off-off-off Strip seedy motels, and gets to work.

But there’s a catch. Amongst the hopeless and often violent encounters in the bars, and out one night on The Strip, he meets Sera. A beautiful, but trapped prostitute, wonderfully played by Elisabeth Shue, who I still think is wasted in the TV roles she always seems to pick up these days. And in that moment, there’s a voltage, not just between the characters, but also between the actors, who are so perfectly cast together that all of the pretense and artifice of the story and the falsities of its location begin to melt away as our attention is drawn with extreme specificity into the intimate space between them. Sera’s guard, as you’d expect given her work, is up, and she’s highly skeptical of Ben’s motives in asking her for dinner. But he’s not a prospective client. He’s just intensely lonely, and in him she sees herself. As they spend more and more time together, their friendship blossoms into romance. But it’s spinning faster and faster, and starting to spin off its axis. Sera’s time with Ben means she’s not working. And when she doesn’t work she doesn’t earn the money needed by her pimp, who’s being pursued by the local mob. Ben’s alcoholism is worsening, especially as he moves towards being a happier drunk with Sera. His health declines, and Sera’s efforts to help him do nothing to weaken his commitment to the plan.

Sera’s frustrations with Ben boil over, who refuses her help even as she pleads with him to seek medical attention for her sake. They split, and as Ben wastes away in the squalor and excrement of his cheap motel, Sera is violently raped by a gang of frat boys, in town for a good time, even if that’s at the expense of someone else and no matter the cost. As Ben nears the end, Sera finally finds him, they make love, and he dies.

Much of the story happens retrospectively through intimate recollections by Sera, in conversation with her therapist. It’s in these scenes where Sera remembers Ben, that she has one of my all-time favorite moments in movies. “I think the thing is, we both realized that we didn't have that much time. And I accepted him for who he was, and I didn't expect him to change, and I think he felt that for me, too. I liked his drama, and he needed me. And I loved him. I really loved him.” The music swells, the scene fades into the credits, and the usually abhorrent Sting’s version of ‘My One and Only Love’ is drowned out by the highly predictable and remarkably consistent sound of me bawling my eyes out.

I came to Leaving Las Vegas a little late, seeing it as a home video rental on VHS in 1997, a couple of years after it was released. But its timing was incredible in paralleling a time when I too was getting my heart ripped out. These days I still listen to the movie’s soundtrack from time to time, and just like the film, it’s a hard thing to absorb, even now, over 25 years later. Both movie and soundtrack take me right back to that time in my life, reopening old wounds, as if a hand from the past is reaching forward in time asking me to take it, again and again. Such is the transformative and transportational power of the movies. A simple line, Sera’s “I really loved him” is a highly efficient time machine, instantly spanning the time between now and then.

Nicolas Cage deservedly won the Best Actor Oscar award for his stunning performance as Ben, but it’s really Shue that’s the star of the movie. Her tender, genuine and troubled depiction of a call girl trapped in a downward spiral of violence and desperation not only mirrors Ben’s decline, but does it in a way that, as the survivor of the story, helps us to understand both their experiences through her memory. We’ve all had friends we’ve loved and lost, and the older I get, the more I hate it. But if we’re lucky enough to have even the briefest of moments of what Ben and Sera had, given all their challenges, and even if those moments don’t come that often in life, that’s still good enough for me. I hope it is for you too.

Popular Reviews