In The Shadow of The Brutalist

Yes, The Brutalist is long. It’s pretentious. It’s ambitious and unapologetically grand. But this is what makes it interesting. It’s a film that forces you to bear witness to an unchecked ego and sit with that discomfort. Far from being a stock tale of genius, the film is a complex (and flawed) meditation on the forces that can elevate and destroy a man.

The Greatest Movie Never Made: Kubrick’s Napoleon vs. Bondarchuk’s Waterloo

In late 1969, Stanley Kubrick was busy. His career-defining 2001: A Space Odyssey had been an enormous directorial and technical success, he was in the middle of editing the dystopian A Clockwork Orange, and beginning to circle what he thought would be his next grand project, a definitive biographic story of Napoleon. Like all Kubrick projects, especially those following 2001: A Space Odyssey, the process for developing the script, and the sheer effort which went into the production was total. For years, Kubrick had planned to create a biographical film of Napoleon’s life, and had engaged hundreds of production staff in gathering as much information as possible about the era. From costumes, interiors, historical records, surviving written evidence, academic historiography, everything was completely exhaustive, and all of it would go into the creation of what Kubrick believed would be one of the greatest historical films ever made.

Beanpole’s Frozen Trauma

The icy Leningrad wind blows through the soulless, gray buildings. The equally soulless, gray people recovering from the immediate aftermath of The Second World War blow through the streets like torn pieces of newsprint. These frigid streets mask the squalid desperation of those who’ve survived, and look to make the transition into what will become the post-war Soviet socialist state. It’s a moment beautifully frozen in time, but also the moment we first meet Iya (played by the incredible Viktoria Miroshnichenko), frozen in place not by the weather, but by the temporary immobility of post-concussion syndrome. Her voice in close-up crackles and she trembles as her muscles spasm. All we hear is a distant ringing, and the drowned voices of the blurred figures she works with in the infirmary. The shot uncomfortably lingers. We are forced to watch ever closer, increasingly drawn into her suffering.

The Satisfaction of Barry Lyndon

I always think of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon as the Kubrick movie everyone forgot. While it has all the signature trademarks of a Kubrick classic, from the emotional detachment that’s so cold it’s cool, to the innovative cinematic techniques, extreme points of tension and beautiful photography, it’s often eclipsed by his films that came before and after it.

For God’s Sake Come Back: The Legacy of Zulu Dawn

Even in an era of reparation, celebrations of Empire are still remarkably commonplace for the English, and there’s a wealth of movies which still regularly air on British television that glorify its unsettling colonial past. The most common of these is Zulu (1964), which introduced Michael Caine to the world and depicts the bravery of around a hundred British soldiers in the overwhelming face of three thousand eponymous Zulu warriors. Quotes from the film have passed into common language, and even today it’s routinely held up as a model of Victorian colonial heroism and conquering of native resistance.

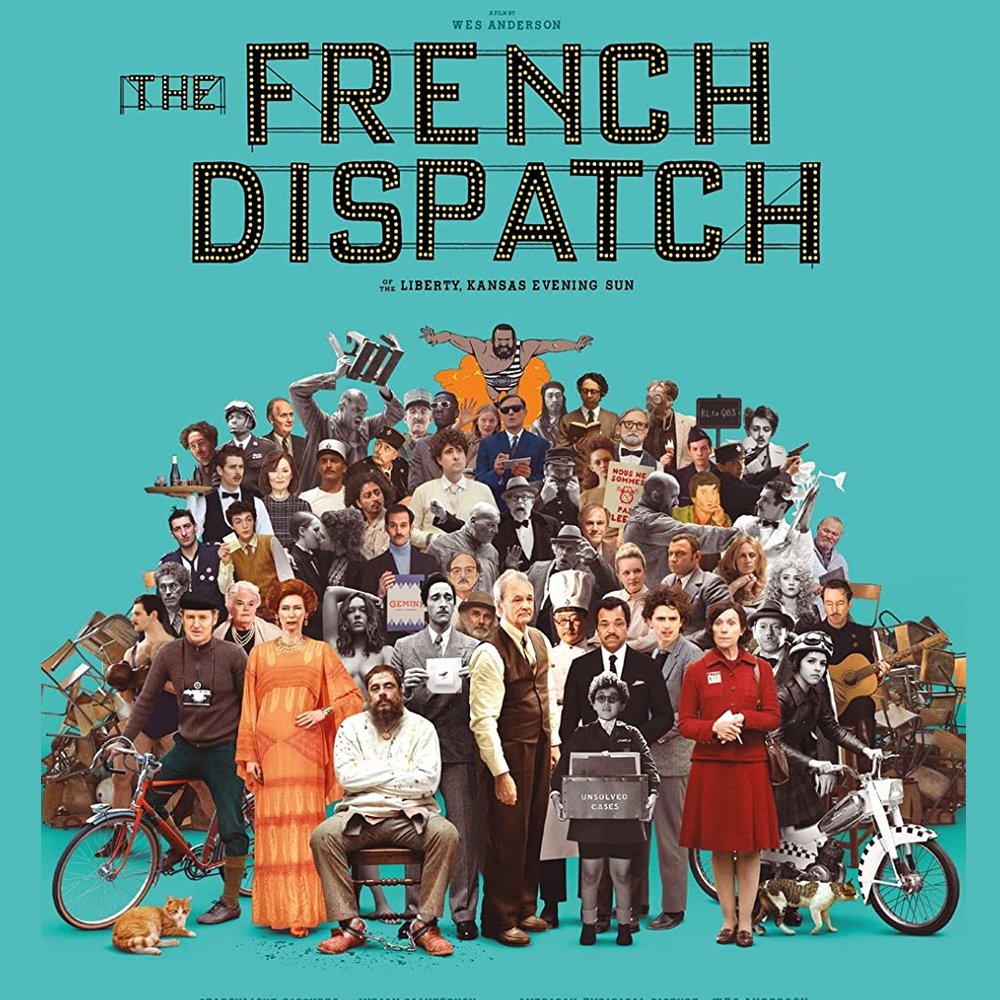

No Such Thing as a Small Role: The French Dispatch

Wes Anderson is capable of more than his usual fantastical endeavours. In his newest film, he creates something entirely different, even from his nine other films of similar style. The French Dispatch, written, directed, and produced by Wes Anderson, is an anthology of several shorter stories tied together through a writer’s room of the fictional newspaper, Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun. Seemingly inspired by The New Yorker, this film is a tribute to journalism and eccentric storytelling.