Menace In The Air: The Opening of 'Once Upon A Time In The West'

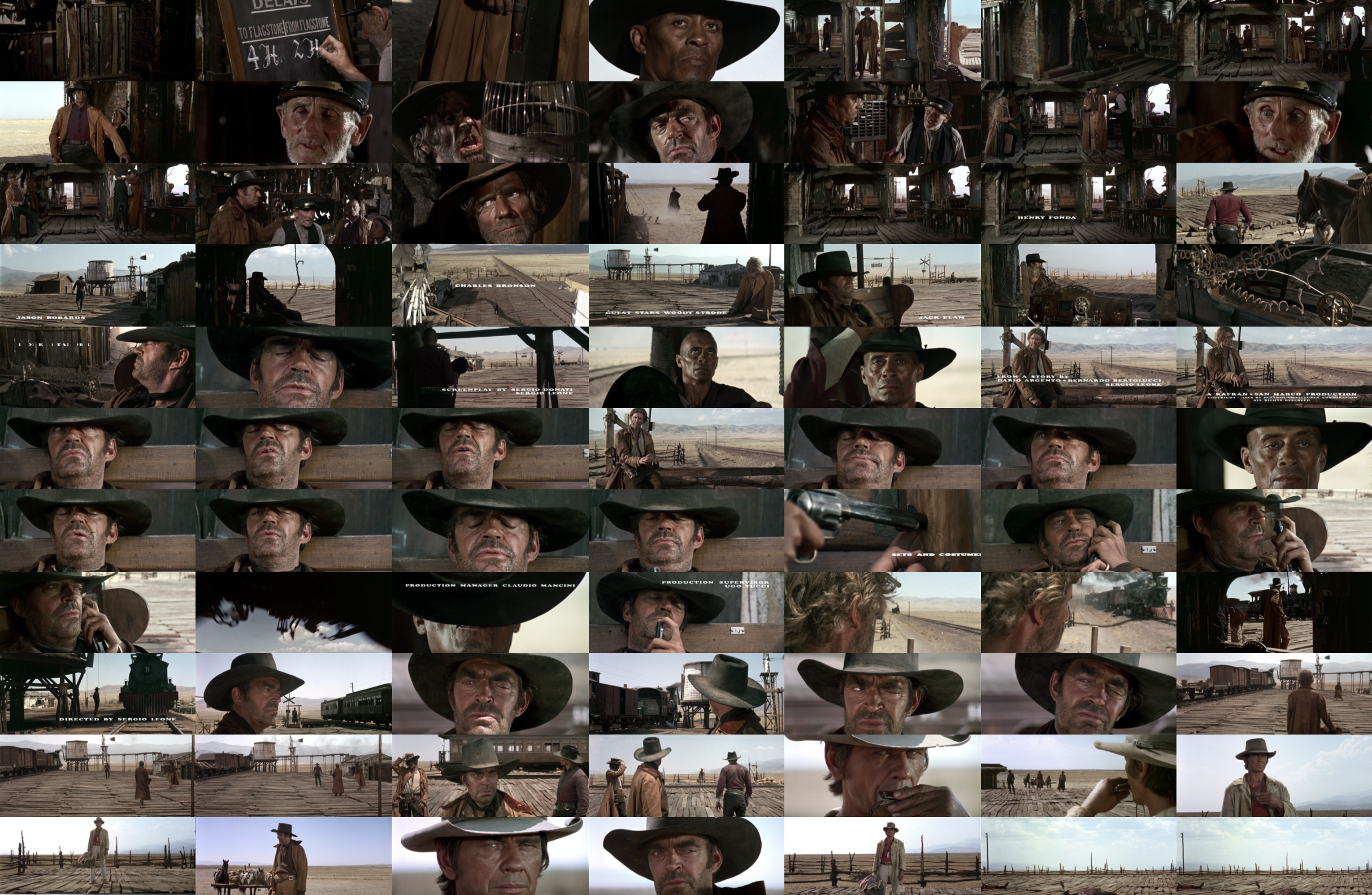

The dust blows forward and the dust blows back, but menace is in the air. Three gunslingers arrive at Cattle Corner, a train station in the middle of the Old West, hours from civilization in either direction, and they mean business. Their business is killing, and business is good.

As with most Spaghetti Westerns made by Italian directors in the sixties, all of the audio is dubbed in later. The only thing we hear is the ominous silence of anxiety and tension, interspersed with the breath of manifest destiny and the approaching progress of the railroad. In the first fifteen minutes of Sergio Leone’s 1968 film, Once Upon A Time In The West there’s scarce dialogue, but what we do hear tells us all we need to know. What’s not spoken speaks volumes. It’s here we meet the three dusters. The three hitmen dressed in their eponymous long, well-worn and weather-beaten coats. Snaky, played by the wonderfully menacing Jack Elam, Stony, depicted by long-time cinematic cowboy Woody Strode, and Knuckles, by Al Mulock. All three are ultimately inconsequential to the larger narrative, but serve to illustrate the ruthlessness of the westward land grab made manifest by the railroad’s expansion west.

Inside each of the dusters is a desperate man. And soon to be inside each of the men will be a bullet. Leone’s attention to detail is his trademark meticulous, and the slow pace of editing, the ominous silence, and the anticipatory looks to the horizon all serve to ratchet up the tension as the killers wait. They spread out. One takes a seat by an old trough, washes his hands and slowly, purposefully cracks his eponymous knuckles. Stony heads to the water tower, which slowly drips, drips, drips on his hat. Snaky gets the most screen time, or rather Snaky’s adversary, a rogue fly who relentlessly tortures his beard and refuses to quit despite Snaky’s continuing efforts. Only his eyes, one of which is lazy, follow the fly, and when it finally settles on the bench beside him, Snaky takes the opportunity to trap it in the barrel of his gun. From here he relaxes as the fly’s wings sing inside the gun, and Snaky smiles a satisfyingly ominous smile. The cracking of the knuckles, the drip of a leaking water tower, and the unrelenting intrusion of the fly draw out the interminable pace of the killers’ waiting, as we wait alongside them.

Their wait is accompanied by the opening credits, which play along with the environment over which they rest. And with a grateful nod to his western hero John Ford’s silent film The Iron Horse (1924), Leone introduces us to the cause of the killers’ scheme, the metaphor for technology and progress, the train. Someone is on that train that’s about to be in the ground. As it pulls to a stop alongside the makeshift wooden platform, Leone’s directorial credits appear and we hear it breathe in labored anguish as it takes rest from its trek through the desert. The train gasps for air as we also hold our breath to see who gets off. But nobody does. A postal worker dumps out a package, and the train begins its journey to the next stop. The dusters regroup, retire, and recognize that they need to settle in for that long wait for the next train.

But as they do, walking towards the camera, and with the train departing screen right, one of composer Ennio Morricone’s signature character themes begins, heralding Harmonica, played by Charles Bronson. In classic Leone tradition, and reminiscent of the standoff finale from his 1966 film, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, Harmonica stands before the three dusters, wheezing into his eponymous instrument before squaring up to them from across the tracks.

In one of the best exchanges of the entire movie, and perhaps of all Leone’s movies, Harmonica asks ‘Where’s Frank?’. The man he’d come to meet, expertly played against type by Henry Fonda and who we later find out, is Harmonica’s true target, we just don’t know why yet. Snaky, again with a menacing tone, responds ‘Frank sent us’. The pace of the edits is still slow, but accelerates as the tension begins to reach its crescendo. We know the end is coming, we just don’t know for whom. Perhaps for the killers. Perhaps for Harmonica. ‘Did you bring a horse for me?’ asks Harmonica, and with his question we already know the answer. Of course they didn’t, but their plan is that he won’t need one in the grave. Turning to the three horses behind him, Snaky again, a smile on his face, quips ‘It looks like we’re shy one horse’. Knuckles and Stony smirk in agreement. And with one of the greatest, most subtle head shakes in film history, Harmonica signals his disagreement as the trademark extreme close-up that characterizes all Leone westerns takes hold. The screen fills with Bronson’s eyes as he wryly, purposefully replies ‘You brought two too many’.

Both sides have dealt their hands, and now it’s time to call. The killers reach for their guns, but of course they’re all too slow. By the time they fire it’s already too late, and Harmonica guns them down in cold blood. Stony gets a late shot off and manages to wound Harmonica, who also collapses, but not fatally like his colleagues. The scene ends with the unrelenting squeal of an old rusty wind turbine. Harmonica gathers his belongings and tends to his arm, and the main narrative of the movie begins.

There’s so much to unpack in these opening minutes, not least of which is that none of it really matters. Harmonica gunning down three of Frank’s men only serves to introduce us to the ruthless survival of his character, and sets up a series of events leading to one of the best revenge stories of all spaghetti westerns. We hear of Frank, but only later do we see how awful he truly is. Harmonica gets his shot at Frank in the end, with Fonda and Bronson at the peak of their acting powers in a truly outstanding duel worthy of any classic finale.

Leone knowingly lets the audience in on the fun too. The titles play and dance around the environments in their distinctive Cooper Black typeface. Contemporary audiences would have recognized Woody Strode from other famous westerns such as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Two Rode Together (1962), the TV show Rawhide (1959-65), and from other sweeping epics such as Spartacus (1960) and Gengis Khan (1965). He also served in the Army Air Corps during World War II, and was one of the first Black American players in the National Football League. Jack Elam, famous for his misaligned eye, caused by a childhood accident, was also a veteran, both in the military but also as a cowboy. He’d starred in High Noon (1952), The Man from Laramie (1955) and The Comancheros (1961). Similar to Strode, he also had a distinguished TV background, again mainly playing characters from the Old West. Contemporary viewers may know him from a famous turn in The Twilight Zone, and from his role in The Cannonball Run (1981). Al Mulock as Knuckles has a sadder end to his story. Leone had used him before in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, and again had him killed, famously by Tuco as he guns down Mulock’s one-armed killer from the bathtub. But struggling with the grief of losing his wife to cancer the previous year, from whom he was already separated, he allegedly turned to drugs to ease his pain. However, with no material means of acquiring them in the shooting location of southern Spain, he jumped out of his hotel room window, still dressed in his duster and cowboy costume. He survived the fall, but not the ride to the hospital, a broken rib puncturing his lung on the bumpy journey. Leone insisted on saving his costume.

Leone also places the sequence in cinematic history for us too. There’s abundant visual references to John Ford’s The Iron Horse (1924) and Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952), and even self-referential elements from his previous Dollars trilogy. Leone had originally intended the three hitmen to be played by The Good, The Bad and The Ugly’s cast of Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach and Lee van Cleef, who would have been especially menacing as one of the dusters. And with their death, a signal to the audience that the past was over, and just like the old west, progress was inevitable. He also tried to cast Eastwood as Harmonica, again without success as Eastwood began to take top billing that year in films such as Hang ‘Em High, Coogan’s Bluff and Where Eagles Dare (all 1968). The man with no name was now known worldwide. He was the second most famous cowboy in the world after John Wayne.

The framework of Harmonica announcing his arrival is a reference to Sterling Hayden’s guitar in Johnny Guitar (1954), the bell on James Stewart’s saddle in The Far Country (also 1954) and the use of the accordion as the railroad gets laid in Night Passage (1957). In The Fastest Gun Alive (1956), knuckle-cracking as preparation for a showdown is on display, and also references Cary Grant’s hands getting crushed by a sinister Martin Landau in Hitchcock’s North By Northwest (1959). Audiences in 1968 would have been aware of these knowing nods, and played along willingly with Leone as he sets the tone for what’s to follow.

Superlatives don’t do any of Leone’s movies justice. Iconic. Epic. Tense. Extreme. Beautiful. Cinematic. None of these words seem to capture how incredible the storytelling is, and this is especially true in the opening sequence of Once Upon A Time In The West. Leone went on to direct Once Upon A Time In America, again a sprawling, multi-generational, sentimental gangster epic that lays down the track for Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Francis Ford Coppola to faithfully follow. But the opening tale of three killers in search of their prey, a relentless fly, a harmonica, and a train that breathes life not only into the west but slows our own breath as we hold it in anticipation of what happens next is so self-contained, so wonderful, that it’s never been matched.

Popular Reviews