Tribeca 2016: The Happy Film

This review is part of the Moviegoer's coverage of the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival.

Shot over six years and taking several months to finish editing, the sophomore opus of Ben Nabors and directorial debut of renowned graphic designer Stefan Sagmeister brings the zest of a Michel Gondry music video to the documentary form and marks the final iteration of a long experiment in self-actualization and wellbeing.

The Happy Film begins with a disclaimer that "This film will not make you happy." A voiceover then announces, "I don't know how this film will begin, but I know how it will end." We see hundreds of yellow balloons lift Sagmeister several meters into the autumn sky, "The End" spelled out in smaller black balloons using the veteran graphic designer's eccentric handwriting. After breaking up with his girlfriend of 11 years, Sagmeister expresses his dissatisfaction doing commercial work and desire to devote more time to personal projects. He begins keeping a diary, and following the advice of a psychologist at New York University, he experiments meditating, undergoing cognitive therapy, and taking drugs, during the course of which we witness three romances and the death of one of the film's co-directors, Hillman Curtis, who passed away in 2012.

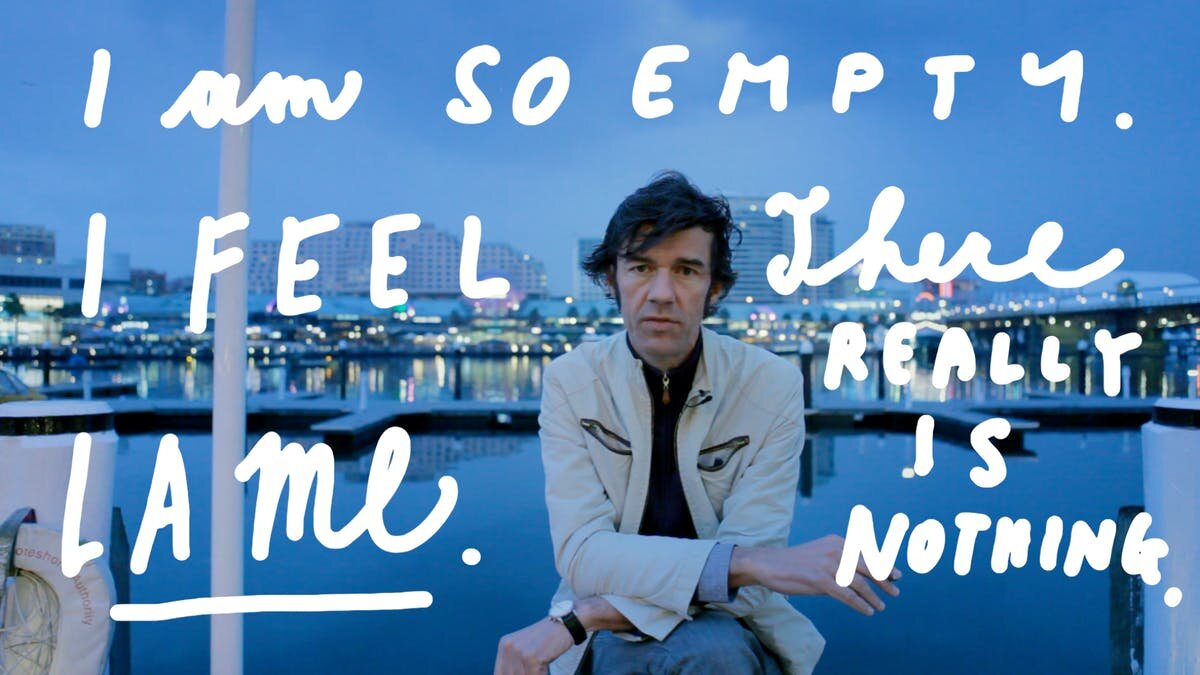

Bespoke hand-lettered typefaces and acoustic guitars strumming over slow motion shots sprinkle the film, which employs a variety of recurring visuals from elephants to shadow puppets, which illustrate a romantic episode recounted by Sagmeister at a meditation camp in Indonesia. Finding meditation creatively unfulfilling and seeking stimulation, he leaves Indonesia and visits a therapist. Sagmeister's third treatment, taking anxiety medication, provides a convenient climax for the narrative, as his ecstatic response sows doubt that he is genuinely interested in marrying a woman he had just started dating while planning a large exhibit at Philadelphia's Institute for Contemporary Art. Realizing that his passion was artificially induced, he breaks off the engagement.

An implicit assumption that any insights Sagmeister achieves are applicable to the viewer could be interpreted either as vanity or as introspection, and since the subject of the film is also one of its directors, the extent to which editorializing shaped his portrayal is unclear. The pursuit of happiness is terrain covered in innumerable coming of age dramas, and if not for its quirkiness and charm, The Happy Film would come across as unabashedly self-indulgent to those uninterested in Sagmeister's private life. When the film is over, audiences will exit the theater having caught a glimpse into the life of one of the world's most influential graphic designers without necessarily having gained any insight into their own.

More an autobiographical portrait than a treatise on happiness, the film nevertheless makes up for weaknesses such as clumsy pacing and competing affects with graphical inventiveness and visual playfulness.