This is All We Are: Anatomic Existentialism

Television is a unique format; whenever a character dies, they are absent not just for the rest of the night, but also in every subsequent plot, lingering as a void over the dramatic structure of the series. And television has not gone for want of ways to maim, deprive, and kill members of its ensemble casts, whether it be the latest massacre on Game of Thrones or the most recent shock death on The Walking Dead. But two shows are particularly notable for their treatment of death. While other shows give us a glimpse of this through haunting absence, no others probe into the base material conditions of our mortality quite like The Knick and Westworld. These shows revel in the dead, the dying, and the injured, going like none other before by so invasively entering the operating room, and into our bodies.

"His life may be said to pour from him in incessant streams"

In arguably one of the most captivating opening scenes in recent memory, director Steven Soderbergh thrusts us into this brutal reality in the pilot of The Knick. Saccharine white doors give to a low gurney bearing an expectant mother. In the moments prior to her sedation, she whispers to one of the attending physicians, “Please save my baby.” Jules, who is overseeing the operation, prefaces the audience much like the introduction to an article in an academic journal: The Patient, presented eight months into her pregnancy with a case of placenta previa. The mother has become a found natural object.

At the start of the surgery, Thack, the show's protagonist, slices the pregnant woman's stomach open, as clots of blood spill out and arms pour over the body: cauterizing, suctioning, controlling. Bits of placenta are extracted. Soderbergh makes quick cuts to the bits hitting a steel pan - one, two, three – as the blood flow increases. Another doctor continues pumping blood, nearing the first pint. Jules mutters under his breath, while a nurse reads heart rates – her pulse pushing the doctors to work faster. She becomes eccentric, then nothing. They look up, the nurse shakes her head. They look to the baby – again, nothing. Jules turns to the audience and utters:

“It seems… It seems we are still lacking. If nothing else, this has been instructive for you all”

Scenes like this are so compelling in part because Soderbergh hired a full-time medical consultant, Stanley Burns, who was on set for every surgery on The Knick. Due to the dynamic nature of the show's visual effects, most of the surgeries had to be shot in one take – it’s difficult to get gushing blood to behave the same way twice. As a result, the actors had to be trained to react like doctors, plugging leaks and suturing wounds as if by second nature. The fact that these are shots were done in one take give the scenes a uncanny dual urgency – the camera and actors must scurry to make the scene work visually, while trying to portray people who are performing with the very same urgency in order to save a life.

In doing so, Soderbergh captures something particular about The Knick's early 1900s era setting that gives the presence of medical practice such a sense of unease. The turn of the century was an explosive time for medical practice, truly the birth of modern medicine. There’s a moment in the episode in which Thack reflects how his father fought in the Civil War, and we’re thrown back to a not-too-distant time when a bullet hole was a death sentence, surely leading to a gangrenous, long-drawn, painful death. At this point, we understand just how revolutionary this era was. Yet as modern viewers, we’re likewise in disbelief at the borderline barbaric procedures that qualify as good practice here; what we’re shown are the very interstitial and fragile stages of man’s relation with body – hernia operations done in basements, skin grafts conducted by sewing one's arm to one's face.

In the short few minutes since the expectant mother of that first scene unwittingly utters her last words, she so rapidly deteriorates from being someone’s loving wife into being a cadaver. Thack reassures himself, “Don’t blame yourself, blame the procedure.” But it’s thoughts like this that transform people into a mass of cartilage and marrow, rather than sentimental beings. And it’s difficult once that process has started not to turn the procedure upon oneself. Jules returns to his study after the failed surgery and promptly shoots himself.

“A beauty supreme, yeah you were right about me, But can I get myself out from underneath this guilt that will crush me, And in the choir I saw a sad messiah, He was bored and tired of my laments, Said, ‘I died for you one time but never again.’” – Brand New, Limosine

Much like the doctors of this era, we're given a glimpse into the vast systemic knowledge of a new medical future, but seem to lack merely the speed or ingenuity needed to reach those lofty promises. We’re shown the explosion of that modern pursuit, where man made secular the body from the self and began to take seriously the probing of his being, but in so doing lost something mystic about humanity.

The Bicameral Mind

This is where Westworld comes in.

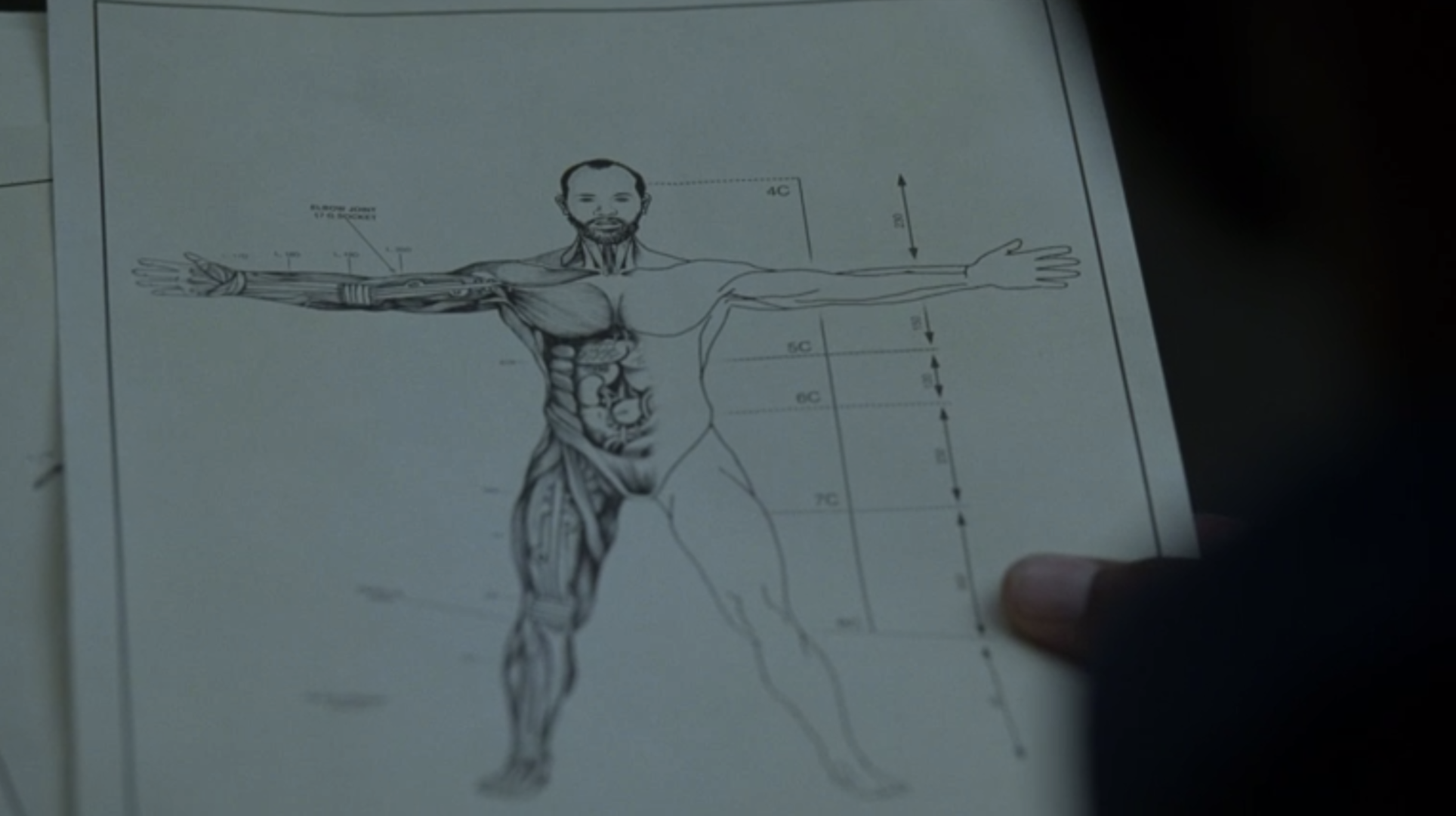

Midway through the season, Maeve demands that Felix, one of the more obliging lab techs at Westworld, take her on a tour through the park’s facilities. As she walks the halls, each floor going through the different stages of Ford’s assembly line, she unwraps her own being: blood (vitality), body, behavior – the principal components of a human, asking, like the ship of Theseus, at which point they became someone’s daughter, someone’s wife, someone’s mother.

Whereas The Knick pulls apart the human condition by dissecting the pieces that make a man, Westworld does the same by connecting the gross aggregates of man, before positing that he is no more than the sum. Both procedures, however, presuppose a certain requisite anatomy of what it is that makes a human. As such, they aren’t different so much as just opposite bounds of our current cultural imagination: the body’s past and the body’s future.

Adopting this perspective, Westworld’s hosts become pioneers of a new anatomy, sufficiently removed from our own that we can view them with a benign curiosity. Throughout the series, hosts injure themselves: Maeve plunges a dagger into her gut to test her faith in the reveries she’s been having, Dolores peels back the skin on her arm to reveal the steel machinery underneath. But while these injuries cause the appearance of 'pain,' and while they emulate the sensation, the actual significance of pain is not in the biological neurons firing, the blood lost, or the mutilations suffered. At the end of the day, their scars heal, their limbs are replaced, and their minds wiped. But these traumas become the gestalt moments that lead to their liberation, realizations that enable them to separate from their creators. They, like doctors, probe deep into their bodies as maps to a material reality, and likewise must come to the same secular terms as surgeons of themselves.

“I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” – Blade Runner

Theories of mind broadly falling under the umbrella of emergentism posit that consciousness is not an intrinsic property of humanity, but rather of the body. The vast and interconnected electrical circuitry of the brain gives rise to innumerable calculations that are for all intents and purposes to us, as finite beings, stochastically indeterminate. The bichameral mind becomes the disjoint between materialist physical processes of cognition and the transcendent voice that emerges from it, more broadly spiritual: the ghost in the machine.

But what pain reveals is that disconnect – that body is separate from mind and not mind from spirit; in essence, that we as hosts, surgeons, and patients are locked in and held hostage to the physical conditions of our body, and to which consciousness is but an affect. The gratuitous images of gore in The Knick and Westworld give rise to the uncanny feeling of an emergent consciousness that perceived itself to be something higher, but could not understand why.

Whereas this realization is rewarded with triumphant liberation in Westworld, in The Knick, there are no masters to overthrow, no walls to look beyond, no documentation to support these questions. Instead, The Knick explores the absurd conclusions of a vividly material world, where after so many hours working at the frayed ends of man’s biological fabric, the workers appear to have found the strings, and have followed them to their inevitable conclusion: Algernon fighting until his iris was knocked loose and he could no longer perform surgery, Gallinger committing his wife to an asylum and having all of her teeth removed in the hope of removing her maladies, Thack disappearing into an addict reverie.

Throughout both shows, we’re shown amnesia as a recurring motif: the memory which resets at the eve of a coming day, the fading sleepless nights, gaslit alleys and opiate hazes. Perhaps, if there is any, this is the conclusion we’re left with: the idea of forgetting as the only way back to normalcy; unconsciousness as the sedate and only possible mode of existence for the generalized body.